|

|

| May 1, 2008 PBN Audio Olympia-L Preamplifier and Mini-Olympia Stereo Amplifier

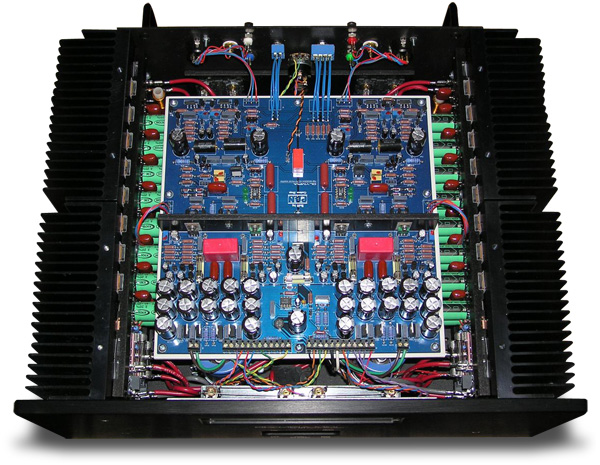

The moment I fired up PBN Audio’s solid-state Olympia-L preamplifier ($12,000 USD) and Mini-Olympia power amplifier ($8500), I let out a "Wow!" of pure delight. The sound was astonishingly vivid, full, and gorgeous. My Sonus Faber Grand Piano Home speakers seemed like big barrels overflowing with sweet, clear sonic rainwater. I’d just finished hooking everything up -- no small task, with four separate runs of my copper-foil speaker wires and another four of proprietary BNC video cables coiled between amp and preamp -- and was taken aback at the tsunami of wonderful sound that poured through the drivers and filled my small listening room. I’d put on an XRCD I’d just bought of Holst’s The Planets, with Zubin Mehta conducting the Los Angeles Philharmonic [JMCXR-0013], and the PBN electronics enlivened my speakers as if, inside them, a circus was going on, complete with elephants and tigers and flaming hoops. It was one wall-rattling Allegro molto. So, just for starters, I’ve already said that I heard sound like clear rainwater, like a tidal wave, like a flaming circus -- three different and inadequate similes to try to account for the powerful effect of the PBN gear in my system. And all of this was with essentially brand-new equipment straight out of the box. To curb my initial excitement, I waited about a month more before jotting down any further sonic observations. But by the time the PBNs’ burn-in had passed 200 hours, my impressions had only deepened and grown more confirmed. This was a very special combination of electronic gear -- clear and powerful, unfazed by symphonic dynamics and complexity, the intricate syncopations of small combo jazz, or the resonant tones and rich harmonies of piano music. History PBN Audio, the fine-electronics wing of the celebrated Montana Loudspeakers company, is the brainchild of Peter Bichel Noerbaek, the Danish-born engineer behind all the design, research, and development for both firms. Noerbaek launched PBN in 2002, after having produced a preamp and a line of power amps for Sierra Audio in the late 1990s. The Sierra power amps were FET/bipolar transistor, cascoded devices that made a strong reputation for themselves among a crowd of cognoscenti, and were built in the PBN Custom Shop at Noerbaek’s headquarters in El Cajon, California. Noerbaek launched the PBN Olympia line at the 2002 Consumer Electronics Show with the Olympia-LX preamp ($20,000) and Olympia-PX power amp ($20,000). Though outwardly similar to the beefy Sierra line -- with the same matte-black, .25" aircraft-grade aluminum chassis and big, backlit frontal meters -- the new electronics were completely different inside: the PX power amp had all J-FET input/MOSFET output, and the LX preamp had J-FET input. Most recently, at the 2004 T.H.E. Show, Noerbaek came up with the slightly less expensive Olympia-L and Mini-Olympia, trickled down from the principles and features developed for the X models and, in terms of price, sitting squarely midway on the list of PBN electronics. Impedance-matched design I’ve always kept my ears open for Peter Noerbaek electronics. For me, they’ve been among the sweetest, least grainy, and highest-resolving solid-state gear out there. For a few years after it was discontinued, I coveted the compact but powerful Sierra Whitney ($2995), with its output of 100Wpc, all in class-A. I paid particular attention at this last year’s CES and T.H.E. Show, as I’d been asked to be on the lookout for review possibilities. When I requested a sample of the PBN Mini-Olympia, Noerbaek insisted I review it with the Olympia-L preamp (linestage only): "They are impedance-matched at 75 ohms," he said. "They complement each other and you just gotta hear it this way." I was in for an audio awakening. Noerbaek told me he’d been introduced to the concept of impedance-matched electronics when he read an interview with Hervé Delétraz of the Swiss audio electronics company daRTzeel. Delétraz was touting the excellence of signal-transfer connections between components designed to have matched impedances -- for example, a preamp designed to have an output impedance of 75 ohms matched to a power amp with an input impedance of 75 ohms. Generally, an audiophile’s amp and preamp have been made by different manufacturers and are often mismatched in terms of impedance. The interconnect between them is often used as a de facto "tone control" to correct the mismatch. However, these interconnects introduce to the transmission line their own intrinsic internal resistance issues, which lead to degraded bandwidth in the final sound. Delétraz argued that impedance-matched components used with impedance-matched interconnects suffer only minute amounts of signal loss that degrades an audio signal. Therefore, besides achieving supreme clarity, impedance-matched cables can be extremely long, as there are no reflections inside the cables to create the sporadic interferences and resistances to the signal that are common with other kinds of connections. This idea wasn’t new, and the technology had been around for over a century -- impedance-matched connections were once widely used in telephone lines -- but Delétraz was the first to implement them in high-end audio equipment. "I read it, and it made so much sense, I just said, I gotta do it," said Peter Noerbaek. From design to execution took about 18 months. He settled on an impedance of 75 ohms for the preamp output and amp input, and then, between them, used four color-coded, 75-ohm bayonet nut connections (BNCs). He didn’t stop there, but also threw in balanced and RCA connections. The Mini-Olympia has a switch on its rear panel so that the input impedance can be set three different ways: 75 ohms for BNC connection, 3.3k ohms for balanced, and 100k ohms for RCA. I mostly used the BNC connections, which were, by far -- by a mile -- the clearest and most transparent. Specifics and operation The Mini-Olympia is a small brute of an amp, weighing a solid 80 pounds and looking every bit Alpha through every inch of its dimensions: 15"W x 8.25"H x 19"D. To help with lifting, Noerbaek has placed a pair of slimline handles on the rear panel, but even with these, the Mini was awkward to load onto my rack’s bottom shelf. It puts out about 150Wpc into 8 ohms, about twice that into 4 ohms. Though it can be bridged in differential mode to supply a single channel of close to 600W into 8 ohms, I used it exclusively as a stereo amp during the two months of the review period. Its power transformer features quad secondary center-tapped windings; rectified, fast-recovery HEXFRED diodes in the main rail-voltage section; and high-quality onboard regulators for the voltage-gain section. The current-gain section features eight pairs of closely matched, complementary MOSFET output devices at 160V/10A per channel, to produce a total gain of 26dB. The Mini’s overbuilt power supply has a capacitance of 200,000µF. Finally, its 1.5kVA power transformer is made by the Canadian company that once also supplied transformers to Krell and Classé.

On the front of the Mini-Olympia are the On/Off switch, a push-to-start switch, and a switch for high- or low-bias settings, depending on whether the amp is being played or idling. The switches snap into position in a satisfying way, and the push-start button pushes back a bit with a springy resistance before the amp powers on with an internal click and its gauges light up. Once on, the Mini gave off a very faint transformer buzz that I could hear if I placed an ear within about 2" of one of my speakers. Otherwise, the amp was inaudible. Perhaps the Mini’s most striking physical features, besides its imposing weight and size, are its two backlit meters -- the right one measures the rail voltage, and the left is a Vu meter set to full bore. The Mini-Olympia’s rear panel has a clean, straightforward layout. The four color-coded BNC jacks provide individual, lockable connections to the pliant video cables that serve as PBN’s proprietary connections between amp and preamp. Between them is a three-position toggle switch for selecting the impedance setting for each type of connection. On the upper left and right are the usual RCA and XLR inputs, and below them two sets of binding posts (with good clearances) to accommodate biamping. Finally, there’s a 20A IEC connection and the fuse lock. Everything worked perfectly and straightforwardly, as it had to -- PBN provides no owner’s manuals for the Olympias. Noerbaek told me they were writing them, but that he assumed that people who bought PBN equipment knew how things worked. The Olympia-L preamp is an all-FET design with an external MPS mini power supply (9.5"W x 4.25"H x 14.25"D) that has a 375VA transformer with 80,000µF of capacitance. The main transformer features quad secondary windings and HEXFRED diodes for rectification. A proprietary, military-grade, 14-conductor connector of 16-gauge Teflon-sheathed silver wire -- a serious umbilical -- joins the power supply to the preamp proper, which measures 18.5"W x 4.25"H x 14.5"D. This main unit houses four independent regulators and provides 20dB of gain. The Olympia-L’s front panel has a blue LED indicator light, a sensor for the Cary-built remote control, a volume control (24 steps), and a switch to select among sources (two Aux, one CD, two balanced). All controls are clearly labeled in white silk-screened letters, demonstrating what Noerbaek calls his "function without frills" approach to exterior design. All can be adjusted manually, but the small plastic remote is far more handy for setting volume and mute. On the Olympia-L’s rear panel are three balanced inputs, two RCA inputs, and balanced, RCA, and the four BNC outputs for the proprietary interconnect system -- which, of course, is impedance-matched at 75 ohms. In operation, the Olympia-L preamp and Mini-Olympia power amp were entirely trouble-free throughout the review period. System The Olympia-L preamp and Mini-Olympia amplifier went into my reference system: Cary 303/300 CD player, Thor TA-1000 Mk.II preamp, Air Tight ATM-2 stereo amp, Sonus Faber Grand Piano Home speakers (90dB/6 ohm), Analysis Plus Solo Crystal Oval balanced interconnects, Verbatim RCA interconnects, and Verbatim Cable speaker cables. I use a Balanced Power Technology Clean Power Center passive line conditioner for the digital source and preamp. The Mini-Olympia was plugged straight into an Oyaide wall outlet with a 20-amp Harmonic Tech Pro AC11 CL-3 Single Crystal Copper power cord on a 15-amp dedicated line. Other power cords were Fusion Audio Impulse and Predator. My equipment rack is a Finite Elemente Signature Pagode. The listening room is fairly small (12’ x 14’ x 8.5’); I listen both in the nearfield and from about 8’ away from the plane described by my speakers’ front baffles. Olympian sound Used together, the Olympia-L and Mini-Olympia created a powerful, detailed, and richly harmonic sound for just about all the music in my collection. Moreover, the Olympias introduced new dimensions in playback for a genre of music I’d neglected in the previous few months: solo acoustic piano and piano concertos. With those recordings, these solid-state components awakened me to fabulously richer tones; to longer, more lifelike, and reverberant sustained harmonics; to faster, more exciting attack transients; and to more -- and more subtle -- bass than I’d heard before. I played a small boatload of such CDs that I’d retired because they sounded too flat, too cold, or simply "too digital" through my system. But through the Olympias I heard attractively complex harmonies, tremendous resolution, and wonderful extension at the frequency extremes. Though midrange warmth seemed not the Olympias’ forte, I’d venture to say that these electronics were completely neutral, vibrantly rendering orchestral strings with appropriate lushness, while large choirs came through purely, without etch, bleach, or glare. The PBN pair seemed an utterly fine complement to my warmish Sonus Faber Grand Piano Homes, bringing out much more than I’d assumed those two-and-a-half-way speakers were capable of. Over two months, I played more than twoscore CDs of piano music, going through a dozen from my Vladimir Horowitz collection, a like number of Mitsuko Uchida playing Mozart concertos, and Pierre-Laurent Aimard performing Beethoven. In each case, I felt I was listening to a private performance in my study. Dynamics were such that I could feel both the expressive passion and the intricate control of each soloist. This was no more evident than with Alfred Brendel’s recording of the Mozart piano sonatas K.310, K.311, and K.533/494 [CD, Philips 289 473 689-2]. Brendel’s expressive yet supremely light touch on the keys evinced all the Viennese subtlety at work in his explorations of the radiant themes of these largely somber pieces. His sweeping chromatic progressions, dramatic dissonances, rumbling trills, and jagged arpeggios sent me into another world. I’d appreciated this music before, but with the matched Olympias performing their magic, I fell into trances over it. Another telling example of the PBN combo’s combined excellence was provided by pianist Leif Ove Andsnes’s recording of the Grieg concerto with Dmitri Kitayenko conducting the Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra [CD, EMI 5 74789 2]. Too often with piano concerto recordings, inadequate or unsophisticated amplification can make the solo instrument sound flat compared to the orchestra, and the pianist’s dynamic range unnaturally compressed or faint, as if it were behind rather than in front of the orchestra. Not so with this disc -- Andsnes’s piano had a lively dynamic range, from the placidly lyrical to the mighty and the boisterous. During the introduction of the Andante maestoso, his left-hand bass notes seemed to seep and shudder through my study’s wooden floor, as if a beast were rousing from benign dreams. I was no longer merely listening to hi-fi, but living utterly in the music. Orchestral music was no less impressive, and for this my listening notes are more analytic. Playing the aforementioned JVC XRCD of Holst’s The Planets, the system rendered the orchestra with great depth and timbral richness, throwing a wide soundstage with fine and lifelike separation and placement of instruments. In the Allegro first movement, Mars, I heard fantastically tight rhythmic snare drums, deep and sonorous midrange notes from the horns and cellos, and strident violins against an oceanic undertone of warmth emerging from the bass viols. Still, it was the fff passages that made my hair stand on end and me feel as though I were on a rocket traversing the solar system. Yet pianissimo passages possessed every delicacy of performance, rendering the intricacies of instrumental interactions with a velvet touch. With the PBNs, I heard both the most dramatic and the sweetest string sounds I’ve ever heard from my system. And in Jupiter, the great fourth movement of The Planets, it was utterly thrilling to hear the theme migrate from the lushness of the first violins to the dark gravitas of the horns. With the paired Olympias providing all of this work’s grandeur, sweep, and fulsome dynamic range, together with delicacy, air, and sweetness, I felt that this was what high-end audio is all about. The Mini-Olympia, even with its relatively modest (for solid-state) 150W, still had much more headroom, dynamic range, and reserve power than I’ve become used to. For example, as a given recording of orchestral or choral music got more dynamic, the Mini-Olympia could ratchet up its output without the soundstage congesting or collapsing and without choral voices becoming a smear of treble glare. This was particularly evident in big choral-orchestral works, such as Ein deutsches Requiem. One of the grandest interpretations of Brahms’s great elegy is that of Herbert von Karajan conducting the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra in 1964 [CD, Deutsche Grammophon 431 651-2]. But until I’d hooked up the Olympia-L and Mini-Olympia to my system, I had never heard all that was on this CD: fulsome bass notes from the organ against titanic orchestral crescendi and sweet, mournful singing from the sopranos of the Wiener Singverein -- all without any of the high-frequency bleach or treble hardness I hear from some solid-state equipment. The PBN combo’s weak spot was its rendering of the voices of solo lyric sopranos. I listened to numerous recital CDs and a handful of full operas, and found that, though the sound was decent in every way, I missed the elegant liquidity and luscious bloom of tubes. Though Angela Gheorghiu (a dark, spinto-like voice) and Renée Fleming (a rich, plummy one) usually came through superbly, the lighter voices of lyric sopranos did not always. Their voices had an undertone of dryness rather than sweetness, and occasionally sounded somewhat thin or hollow, particularly on sustained top notes and during glissandos. On Kate Royal’s eponymous CD [EMI Classics 946 3 94419 2], for example, as she sang Debussy’s "Air de Lia," from the cantata L’enfant prodigue, though the orchestra of the Academy of St. Martin-in-the-Fields, as conducted by Edward Gardner, had all sumptuousness in its strings and a sweet warmth to its woodwinds, Royal’s own tremulous voice sounded the faintest bit chalky to me, its tone not entirely apt for this lyric plaint of a mother bemoaning the absence of her prodigal son. This is not to say that the Olympias had no finesse, or a limited timbral palette -- quite the contrary. These electronics were smashing with recordings of the subtle interplay and jump of small jazz combos. Their speed, PRAT, and ability to swiftly paint the leading edges, sustained harmonics, and trailing nimbuses of multiple, rapidly played 16th-notes seemed perfectly suited to Joe Pass’s Portraits of Ellington, a 1974 trio session produced by Norman Granz [CD, Pablo PACD 2310-710-2]. In "Satin Doll," Pass’s guitar obbligatos ran liquid, mellow, and silky, in great, ringing runs. Ray Brown’s standup bass was swinging, resonant, and percussive, his fretwork so articulate it felt absolutely tactile. Finally, I could tell that Bobby Durham’s initial pattering brushwork on the snare gave way to a staccato clattering of his ride cymbals with a plain stick, his timing accomplished with complete authority through the changes. And, when he hit the crash cymbal, I could delightedly distinguish whether his stick was on the cymbal’s rim or its center metal, as the individual signatures of each stroke and its placement came through on time and with coherence, the wooden attack transients morphing within a nanosecond into a cowbell-like clank or a rim-chatter, until taken over by the sustained but achingly slow diminishing shimmer of brass. Rock and blues voices and instrumentals also fared extremely well with the PBN Audio combo. The Luckys-with-bourbon quality of Susan Tedeschi’s blues voice came through from her Live from Austin TX [New West 7396-6065-2], the soundtrack of a concert originally broadcast on PBS’s Austin City Limits. Often a hoot’n’holler singer whose wails have more than a touch of Janis Joplin, Tedeschi can sometimes sound like Bonnie Raitt on steroids. But on John Prine’s "Angel from Montgomery," Tedeschi kept her powers in reserve, much like the PBN electronics themselves on a piece like this, accenting the lightly swooping flats and sharps of the country tune and featuring the dusky midrange of her voice. It’s an altogether lyric yet down-home performance; the Olympia combo put Tedeschi’s voice forward of the band in club-like fashion, just right of center, with drums and organ to the right rear, fiddle to the left, and guitars and bass at midstage -- all with a rightness of scale and placement. The recording isn’t overly EQ’d, so the liveness of the performance came through, even before the audience’s applause drifted in and Tedeschi modestly rasped, "Thank you so much ev’ybody." Conclusion Listening to the PBN Olympia-L and Mini-Olympia enlarged my appreciation for music, broadening a sonic palette I’d thought already discerning enough. The PBNs introduced me to levels of articulate power and to subtleties of sound that had been missing from my listening. I’d dwelt in smaller sonic vales and villages until the PBNs arrived to guide me to a wider world of audio awareness and a deeper pleasure in listening to music. While I felt more comfortable listening to operatic and choral voices through the liquidity and naturalness of my reference combination of tube preamp and amp, I’m going to miss the PBNs’ effortless dynamics, immense scale of sound, and superb ability to present exquisite musical detail. Never have piano and orchestral music, rock, blues, and jazz sounded better or more thrilling in my listening room. Never has one set of electronics made me sit up and question what had seemed an immutably stark line of connoisseurship dividing the aficionados of glass and sand amplification. PBN Audio’s Olympia-L and Mini-Olympia are well engineered and impressively built assaults on this division. They combine much of the grace and finesse of tubes with the power, precision, and effort-free maintenance of the best of solid-state. And in terms of pure clarity, I’ve heard nothing better. ...Garrett Hongo Olympia-L Preamplifier PBN Audio E-mail: peternoerbaek@pbnaudio.com

Ultra Audio is part of the SoundStage! Network. |