|

| December 1, 2007 Beethoven Chamber Music Bonanza

While the public may have regarded these works as "violin sonatas," Beethoven actually designated most of them, including the monumental "Kreutzer" Sonata in A major, as being "for piano with violin accompaniment." The bottom line is that mere "accompaniment" is out of place here: this is music that requires a full partnership. In the very first recording of the cycle, made under a subscription arrangement back in 1935-1936, the beloved violinist Fritz Kreisler was partnered with the pianist Franz Rupp. While Rupp was indeed well known as an accompanist -- he was particularly associated with the great contralto Marian Anderson -- he also had a sterling reputation as a chamber music player, and more than 40 years after recording the Beethoven sonatas with Kreisler he recorded them again with the Japanese violinist Takaya Urakawa, who acknowledged him as his mentor in this exalted repertory. Among other recordings of these sonatas over the years have been those by Zino Francescatti with Robert Casadesus, by David Oistrakh with Lev Oborin, Itzhak Perlman with Vladimir Ashkenazy, Yehudi Menuhin with Wilhelm Kempff, Isaac Stern with Eugene Istomin, Gidon Kremer with Martha Argerich. All of these have had their attractive points, but in none has the partnership seemed so complete and so all-round convincing, from the three sunlit sonatas that make up Op. 12 to the masterwork in G major (Op. 96, contemporaneous with the "Archduke" Trio) that brings the cycle to its close.

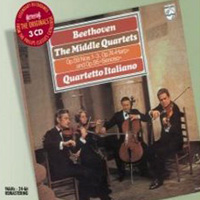

Grumiaux and Haskil, in short, were an out-and-out dream team in this music, to which they brought both intellect and passion, both spontaneity and elegance, and always a feeling of real give-and-take. This is without question one of the most important reissues of recent years. Decca has done a fine job with these early-stereo recordings (taped in 1956 and ’57), and has made them available at a budget price, in a space-saving box with paper sleeves for the three CDs. Robin Golding’s annotation is concise but tells us everything we need to know about the music. If you already have other recordings of some or all of the ten sonatas, this economical package should make the duplication pretty painless -- and these are the performances you will come back to again and again. Curiously, the number of recordings of the complete cycle of Beethoven’s string quartets over the years is conspicuously greater than that of the violin-and-piano sonatas. The Budapest, Végh and Hungarian quartets went through the entire cycle more than once; the Coolidge Quartet was founded (at the Library of Congress, in the late 1930s) for the express purpose of performing and recording this cycle, and virtually every notable foursome active since World War II has recorded it at least once. Not only have there been more recordings of the quartets, but the quartets themselves are more numerous than the sonatas, and there is that question of whether the Grosse Fuge should stand alone, as Beethoven finally left it, or serve as finale to the Op. 130 Quartet, as he originally intended. There are, then, more factors to be considered in choosing an integral recording of the quartets. Two very reasonable choices, though, would be the digital recording by the Talich Quartet, on the Calliope label, which seems to have become a little hard to find lately, and the similarly convincing one from the 1970s by the Quartetto Italiano on Philips, which has seldom been out of the active catalog and now has reappeared in a new remastering.

In this new edition we no longer have the easy option of choosing between the Grosse Fuge or the replacement finale to end Op. 130 on the same disc -- but that replacement was Beethoven’s own final decision, so there is no real loss in having the Grosse Fuge on a different CD, and there is a perceptible gain in sound quality. Another benefit, for some collectors, is that now you needn’t buy the entire nine-disc cycle all at once: the cycle in its present edition comes in three separate three-disc sets: Early Quartets (Op. 18), 475 8252 6; Middle Quartets (Opp. 59, 74, 95), 475 8503 9; Late Quartets (Opp. 127, 130, 131, 132, 133, 135), 475 8685 2. But I think anyone who hears any part of this cycle will want all of it. Listeners who really love these phenomenal works may not be content with only a single version -- and that, when you think about it, can only add to the appeal of this magnificent remembrance of one of the 20th century’s greatest chamber-music ensembles. ...Richard Freed

Ultra Audio is part of the SoundStage! Network. |

The Philips label, which has given us a

conspicuously high quotient of distinguished recordings since its first appearance in

1953, eventually became part of the Decca Group, and now some of those distinguished

Philips recordings are reappearing under the Decca label, while others continue to

reappear on the Philips label itself. In the last several months we have had splendid

reissues of two major sectors of Beethoven’s chamber music from the Philips back

catalog, one on Decca, the other on the original label. Finding the integral set of

Beethoven’s ten sonatas for violin and piano, with the violinist Arthur Grumiaux and

the pianist Clara Haskil, one of the glories of the Philips catalog, suddenly transferred

to Decca may be mildly confusing to some collectors, but it is a matter of very little

consequence, after all, in the enormously welcome return of this truly indispensable set

[Decca 475 8460, three CD].

The Philips label, which has given us a

conspicuously high quotient of distinguished recordings since its first appearance in

1953, eventually became part of the Decca Group, and now some of those distinguished

Philips recordings are reappearing under the Decca label, while others continue to

reappear on the Philips label itself. In the last several months we have had splendid

reissues of two major sectors of Beethoven’s chamber music from the Philips back

catalog, one on Decca, the other on the original label. Finding the integral set of

Beethoven’s ten sonatas for violin and piano, with the violinist Arthur Grumiaux and

the pianist Clara Haskil, one of the glories of the Philips catalog, suddenly transferred

to Decca may be mildly confusing to some collectors, but it is a matter of very little

consequence, after all, in the enormously welcome return of this truly indispensable set

[Decca 475 8460, three CD]. Grumiaux, an exceptional

representative of the Belgian school of violinists, was not a flashy player, but

definitely an elegant one -- and elegance in his case went hand in hand with

straightforward, unselfconscious communicativeness. In the area of Beethoven, he was a

particularly persuasive champion of the great Concerto (his recording with the

Philharmonia Orchestra under Alceo Galliera still tops many a connoisseur’s list),

and with his string trio he left us incomparable recordings of the early but substantial

works for violin, viola and cello. Clara Haskil never achieved celebrity status in the

ordinary sense, but she was adored by fellow musicians. She avoided showpieces altogether,

focusing on Mozart, Schubert, Beethoven and Bach; there is no question at all about her

being a full and equal partner with Grumiaux, or her ability to lead the way when the

music calls for it.

Grumiaux, an exceptional

representative of the Belgian school of violinists, was not a flashy player, but

definitely an elegant one -- and elegance in his case went hand in hand with

straightforward, unselfconscious communicativeness. In the area of Beethoven, he was a

particularly persuasive champion of the great Concerto (his recording with the

Philharmonia Orchestra under Alceo Galliera still tops many a connoisseur’s list),

and with his string trio he left us incomparable recordings of the early but substantial

works for violin, viola and cello. Clara Haskil never achieved celebrity status in the

ordinary sense, but she was adored by fellow musicians. She avoided showpieces altogether,

focusing on Mozart, Schubert, Beethoven and Bach; there is no question at all about her

being a full and equal partner with Grumiaux, or her ability to lead the way when the

music calls for it.  This Quartetto Italiano earned a

remarkable level of respect in its 35 years of activity. Following the replacement of its

original violist in 1946, a year after its founding, its personnel remained unchanged

until 1980, when, faced with the possibility of a second replacement, it was simply

disbanded. The violinists Paolo Borciani and Elisa Pegreffi, the violist Piero Farulli,

and the cellist Franco Rossi performed their entire repertory from memory. Their every

performance -- or in any event every performance they committed to recording -- suggested

nothing less than total-immersion conviction: it was all about the music, not about the

performers, who had an uncanny ability to zero-in on the music’s core. Their

Beethoven was reissued on CD a dozen years ago in one of those space-saving boxes with

paper sleeves, like the packaging of the Grumiaux/Haskil sonatas, and anyone who has that

edition [454 062, ten CDs] may congratulate himself and continue enjoying it; but

Philips’s new edition -- under its own label this time, and in conventional jewel

boxes -- has a somewhat richer, more vibrant sonic character, rather more like the

original LPs, and now has the six late works fitting snugly on three CDs instead of the

four they took up in the earlier box.

This Quartetto Italiano earned a

remarkable level of respect in its 35 years of activity. Following the replacement of its

original violist in 1946, a year after its founding, its personnel remained unchanged

until 1980, when, faced with the possibility of a second replacement, it was simply

disbanded. The violinists Paolo Borciani and Elisa Pegreffi, the violist Piero Farulli,

and the cellist Franco Rossi performed their entire repertory from memory. Their every

performance -- or in any event every performance they committed to recording -- suggested

nothing less than total-immersion conviction: it was all about the music, not about the

performers, who had an uncanny ability to zero-in on the music’s core. Their

Beethoven was reissued on CD a dozen years ago in one of those space-saving boxes with

paper sleeves, like the packaging of the Grumiaux/Haskil sonatas, and anyone who has that

edition [454 062, ten CDs] may congratulate himself and continue enjoying it; but

Philips’s new edition -- under its own label this time, and in conventional jewel

boxes -- has a somewhat richer, more vibrant sonic character, rather more like the

original LPs, and now has the six late works fitting snugly on three CDs instead of the

four they took up in the earlier box.