|

| March 1, 2008 A Double Rescue for the Dohnányi Suite

But those who have acquainted themselves with this marvelous work are few in number, because our orchestras do not perform it. There have been fewer than a dozen recordings of it since the earliest one, made by Frederick Stock and the Chicago SO for Victor in December 1928, and none has remained in circulation very long. This frustrating situation naturally suggests a candidate or two for this department, and must raise some curiosity about the source of this remarkable work. Erno Dohnányi, known more widely as Ernst von Dohnányi (1877-1960), was enormously respected in his time, and regarded as the all-round most important Hungarian musician since Liszt. He may not have known Liszt, but he did know Brahms, who arranged for the young composer’s Op.1, a Piano Quintet, to have its premiere in Vienna. Dohnányi was an outstanding pianist and a notable conductor and administrator as well as a composer. He commissioned and introduced works of his friends Bartók and Kodály in Budapest between the two World Wars, and he taught the pianists Géza Anda, Annie Fischer and György Solti. In his last years he taught at Florida State University, and recorded as pianist for both Remington Records and EMI. Dohnányi’s catalog of works runs to only 48 opus numbers. What has been available for listening indicates a consistently high level of craftsmanship, imaginativeness and tastefulness -- but we hear very little. While both of his piano quintets and one or another of his three string quartets turn up occasionally on chamber music programs, and perhaps a dozen of his big works have been recorded, only two of his compositions may be said to have taken even a peripheral place in the so-called standard repertory: the witty and brilliant Variations on a Nursery Song, for piano and orchestra (dedicated, in 1915, "to the enjoyment of lovers of humor and to the annoyance of others"), and the remarkable Serenade for string trio, composed at age 25. There has been a movement, at least in the form of recordings, to make his symphonies and concertos better known, but it has not made much of an impact. Even the eminent conductor Christoph von Dohnányi has shown little interest in his grandfather’s music, though he did record the Nursery Variations with Earl Wild and the New Philharmonia Orchestra for Reader’s Digest more than 40 years ago. (That stunning performance is now on Chesky CD-13, together with Wild’s recording of the big Tchaikovsky Concerto.) The Suite in F-sharp minor was composed about midway between the early Serenade and the Nursery Variations; Dohnányi himself conducted the premiere in Budapest in 1910. Stock’s recording remained the only one until after WWII, when Sir Malcolm Sargent recorded it with the London Symphony Orchestra for English Columbia and Alfred Wallenstein did with the Los Angeles Philharmonic for American Decca. Both of those versions were transferred from 78s to LP, but had rather short shelf lives. Wallenstein, as principal cellist of the Chicago SO when Stock recorded the piece, must have fallen in love with it when he played those melting solo passages. He was not the only American conductor to champion the Suite. Milton Katims conducted it in his appearances with Toscanini’s NBC SO, and recorded it with his own Seattle SO. Mester, who recorded it with the West Australian SO -- a CD that had a very limited circulation in America -- and continues to perform it with some frequency; next winter he will give several performances of it: with the Louisville Orchestra on January 16 and 17, 2009, and in Naples, Florida, February 26-March 1. Sargent remade the work with the Royal Philharmonic in the stereo area and that recording was revived on CD for a bit. More recently, the Hungarian pianist and conductor Tamás Vásáry recorded the Suite with his Budapest SO on Hungaroton HCD 31637, which includes also Dohnányi’s Konzertstück for cello and orchestra (Csaba Onczay, soloist) and the pithy Symphonic Minutes, but this appears to have been imported in rather limited quantities. An older recording of the Suite that was in broader distribution and now remains unforgettable is the one made early in the LP era by Robert Irving and the Philharmonia Orchestra. It appeared in America some 55 years ago on one of the last of the RCA Bluebird LPs [LBC 1090], disappeared following the severance of that company’s long trans-Atlantic arrangement with EMI. This conductor was most strongly identified with ballet music: he succeeded the legendary Constant Lambert as musical director of the company known now as the Royal Ballet, and ended his career in the same position with the New York City Ballet. Very few of Irving’s splendid recordings for HMV and Decca have been revived on CD, and if any more were to be reissued now they would surely be those he made of ballet music; but he did record a few concert works with the Philharmonia, and his account of the Dohnányi Suite would have to be on any serious list of "keepers." Just now, however, we have a much more recent recording from a totally unexpected source that might claim instant "keepers" status. It again involves an American orchestra under an American conductor; if it does not entirely efface affectionate memories of Robert Irving’s account of the work, it has to be acknowledged as sharing its lofty position, and it comes with the advantage of 40 years’ advances in the art of sound recording.

(To clarify the situation, very briefly: Leonard Slatkin made numerous recordings for RCA Victor with the Saint Louis SO between 1984 and the end of his tenure with that orchestra 12 years later, by which time many of those recordings had been dropped from the active catalog. RCA simply never issued the one under discussion here. With the arrival of Mr. Slatkin’s successor, Hans Vonk, the Saint Louis SO began recording its concerts live on its own label, Arch Media Archives. Eventually the Vonk recordings on Arch Media were taken up by the Dutch company PentaTone for international distribution; at present both PentaTone’s own SACD series and the acquired Arch Media items ("Redbook" all) are distributed in North America by Naxos. Arch Media did not concern itself with the reissue of recordings made for RCA or other commercial labels, and AAM has not taken on any of Hans Vonk’s Arch Media recordings.) This belatedly issued Dohnányi Suite turns out to be one of the finest performances Mr. Slatkin recorded in Saint Louis. It glows with a warm-heartedness, enthusiasm and sheer orchestral brilliance that reflect the character of the music itself, and it benefits from sound that is not only contemporary but truly first-rate, as do the bracing accounts of the Bartók and Kodály. The tray card, incidentally, bears the note, "In fond remembrance of Joanna Nickrenz and William Hoekstra." They were respectively the producer and the engineer for most of Mr. Slatkin’s Saint Louis recordings for RCA, and I believe the Dohnányi may have been the last one they made together. The documentation here is not in the same class as the performances or the sound: there are factual errors and typographical untidiness, and more than half of the insert is given over to distended blurbs and a blurred photograph of what can only be assumed to represent the SLSO on its home stage in Powell Symphony Hall. But one doesn’t buy a recording for its reading matter, and AAM is to be congratulated and roundly thanked for rescuing this fine account of the Dohnányi Suite from oblivion. If you haven’t acquainted yourself with this endearing work, it’s time you did; this is the best way to do that now, and it is likely to remain so for some time. If it means duplicating one or both of the other pieces on the CD, don’t let that deter you: the delicious Dohnányi alone provides more than full value for your investment, with an assured dividend every time you return to it. ...Richard Freed

Ultra Audio is part of the SoundStage! Network. |

Anyone who has ever heard Dohnányi’s

orchestral Suite in F-sharp minor, Op.19, must wonder about the incredible neglect of so

substantial, brilliant and altogether ingratiating a work. There is not a single empty

gesture in its half-hour span. Its four movements -- a dazzling Andante con variazioni,

a sly and bristling Scherzo, a lyric and songful Romanza, a rumbustious,

exultant concluding Rondo (with a big, sweeping waltz and castanets) -- call to

mind the pianist Artur Schnabel’s reference to the Schubert sonatas as "a safe

supply of happiness." The piece is pure enchantment, with its abundance of good

tunes, imaginative orchestral coloring (including some delicious solo passages for

clarinet and cello), its prevailing sense of fantasy, remarkable range of mood, and

unforced charm.

Anyone who has ever heard Dohnányi’s

orchestral Suite in F-sharp minor, Op.19, must wonder about the incredible neglect of so

substantial, brilliant and altogether ingratiating a work. There is not a single empty

gesture in its half-hour span. Its four movements -- a dazzling Andante con variazioni,

a sly and bristling Scherzo, a lyric and songful Romanza, a rumbustious,

exultant concluding Rondo (with a big, sweeping waltz and castanets) -- call to

mind the pianist Artur Schnabel’s reference to the Schubert sonatas as "a safe

supply of happiness." The piece is pure enchantment, with its abundance of good

tunes, imaginative orchestral coloring (including some delicious solo passages for

clarinet and cello), its prevailing sense of fantasy, remarkable range of mood, and

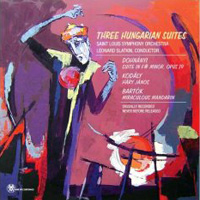

unforced charm. Fifteen or 16 years ago, toward the end

of his tenure with the Saint Louis SO, Leonard Slatkin was persuaded to perform the

Dohnányi Suite. He and his musicians liked the work enough to take it on a cross-country

tour, and then he reintroduced the piece to New York in his concerts with the

Philharmonic. One of his last recordings in Saint Louis was of this work, which was to be

combined with the suites from Kodály’s Háry János and Bartók’s Miraculous

Mandarin on a CD headed "Three Hungarian Suites." But RCA Victor never

issued that CD, and it is only now that AAM, a Saint Louis company with connections to the

orchestra, licensed this material from Sony-BMG and has brought it out for the first time,

under the heading originally devised for it [AAM 37101 37862].

Fifteen or 16 years ago, toward the end

of his tenure with the Saint Louis SO, Leonard Slatkin was persuaded to perform the

Dohnányi Suite. He and his musicians liked the work enough to take it on a cross-country

tour, and then he reintroduced the piece to New York in his concerts with the

Philharmonic. One of his last recordings in Saint Louis was of this work, which was to be

combined with the suites from Kodály’s Háry János and Bartók’s Miraculous

Mandarin on a CD headed "Three Hungarian Suites." But RCA Victor never

issued that CD, and it is only now that AAM, a Saint Louis company with connections to the

orchestra, licensed this material from Sony-BMG and has brought it out for the first time,

under the heading originally devised for it [AAM 37101 37862].