|

| October 1, 2007 Ultra Sounds: Full Disclosure or Postproduction Sweetening? If you believe that a chain is only as strong as its weakest link, then no amount of tweaking of an audio system will improve the sound of a mediocre recording. This logic is independent of formats. An SACD recording, for example, can sound as if it was recorded in a glass room if the producers of the recording don’t know what they’re doing; and, contrary to what some audiophiles may believe, a correctly engineered, 16-bit/44.1kHz CD recording can approach the sonic clarity of an SACD. No matter the format, noise in will always equal noise out. What constitutes correct engineering? Audiophiles and music producers have their opinions, and it’s that bottomless well of opinions and interpretations that feeds the careers of thousands of music producers, many of whom deviate from what science would consider "accurate" because it defines the unique sonic fingerprint they impart to a project. U2 didn’t pick the producing team of Brian Eno, Daniel Lanois, Flood, and Steve Lillywhite for the heck of it. They chose them because they were looking to fashion a particular sound for the groundbreaking rock classic Achtung Baby. Even if a recording is fortunate to be touched by the hand of a master, this doesn’t mean that the playback gear will be up to the task. Distortion can develop in the electrical path of a CD player or the mechanical movement of a speaker cone. These distortions are also at the mercy of their products’ designers. Many audiophiles delight in the "warmth" of tubes -- but is that warmth accurate? Now we’re getting into the religion of the hobby, where all bets are off, and the subjective emotional value individuals place on their equipment trumps fidelity to the original sound. But it isn’t my goal to convince you that one amplifier may sound better than another, or that the work of Brian Wilson is eclipsed by the genius of Roger Waters. I’m here to help sort out the differences between so-called audiophile recordings and commercial studio recordings. I will stick with CDs because I believe that, regardless of what your system costs, a 16-bit/44.1kHz compact disc is still capable of reproducing beautiful, natural music. Those who believe that CDs are compromised probably don’t realize that most of them are engineered to sound best on mediocre audio systems, such as those installed in cars. They sound bad not because the engineers and producers didn’t know what they were doing, but because most people listen to their favorite tunes on portable stereos, car systems, and MP3 players whose primary design parameters were not fidelity, but convenience and low cost. Never underestimate the inexperience of those who feel empowered by readily available software -- the ability to wield a hammer doesn’t make you a carpenter, and downloading mixing software from the Internet doesn’t make you a talented producer. I hope this column can provide a reference with which you can save money and your sanity. Music lovers tend to obsess over the viability of the medium and equipment, so it can be liberating to know that that ten-year-old recording of your favorite jazz group will sound as good on your iPod as the new "remastered" version. Not every remastering is done to please the music lover. Many are released to sell back catalog once again, and thus fill the pockets of floundering artists and their record companies. Mobile Fidelity, one of the leading producers of remastered editions of older recordings, believes that the best remasterings reveal the soul and artistic intent of the original recordings. Where other companies add a unique coloration to the sound, the folks at the Chicago-based company trust in absolute transparency. Using proprietary electronics such as their Gain 2 System, MoFi strives to retrieve from the master tape all the nuances and notes that may not have made it onto the commercial release. Two of the qualities that suffer most in commercial pop and rock recordings are dynamic range and frequency response. The wider the dynamic range -- i.e., the greater the difference between an album’s loudest and softest sounds -- the more room the producer has to preserve the contrast between the timbres of different instruments and retain the natural tonality of the human voice. Unfortunately, recordings with wide dynamic range can wreak havoc through consumer products that lack the power required to reproduce them. The result is distortion not unlike the sound of a paper bag being manhandled. To prevent this, the audio signal is passed through an electronic compressor, which reduces the musical peaks. Dynamic Range Compression (DRC) is used during mixing to normalize the dynamic contrasts between instruments; for instance the dynamic swing of a drum set could easily overshadow the smaller dynamic range of voices or acoustic guitars. The textures of the sounds of human voices and instruments can also be compromised by a constricted frequency response. Many consumer products are unable to reproduce the frequencies at the extremes of the bass and treble ranges, so filtering is used to limit them. To mitigate the destructive effects of these limiting techniques, producers will mix a recording to favor the mid-frequencies, which, with any luck, will preserve the bulk of the artists’ intent.

The sound remains natural until the dynamic swings of Ronstadt’s voice start to climb. This singer has never been afraid to use her healthy set of vocal cords to convey desperation and anger, and here is where the MoFi edition gets edgy. Prolonged listening caused my ears to ache and listening fatigue to set in. I’m not sure whether this was due to the remastering process, or to microphone distortion during the recording session that had been covered up by compression in the original mastering. Repeated listening to the original release did reveal what sounded like attenuated brightness. This makes sense, considering MoFi’s commitment to full disclosure of the original. The downside is that you also inherit the sonic baggage of the sonic compromises made by the original producers and engineers, which is one argument for adding some postproduction sweetening to the mix. What good is it to be true to the source if such fidelity compromises your enjoyment? Which brings us back to why audio is such a personal, even a spiritual pursuit. Some of us want total disclosure no matter the cost; others, for the sake of greater appreciation of the music, prefer some editorializing. It also speaks to my original statement: No matter how good or transparent your system is, the weakest link in the chain is the recording itself. Let’s hope we find some recordings that not only do justice to our setups, but also offer our ears enjoyable experiences. ...Anthony Di Marco

Ultra Audio is part of the SoundStage! Network. |

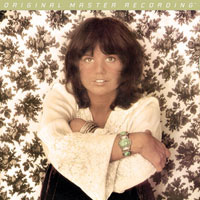

Comparing the original 1973 CD release

of Linda Ronstadt’s Don’t Cry Now with Mobile Fidelity’s new

remastering of it shows how not-so-subtle differences can separate a remastering from the

original. The first thing I noticed was the MoFi’s more expansive soundstage. At

normal levels, Ronstadt’s distinctive voice is more open and crisp, and appears more

forward in the mix, with lifelike height, presence, weight, and harmonic texture. Many

people perceive harmonic texture as a sweetness, or euphonic quality. Here, both

Ronstadt’s voice and the guitar, on such tracks as "Love Has No Pride" and

"Desperado," exhibit a richer harmonic tone than the standard release. This is

not surprising -- DRC can effectively mask overtones. This quality gives the MoFi remaster

a more involving, more spine-tingling, and therefore more enjoyable sound. Vocal

intelligibility is also improved. This makes sense -- the natural overtones of plosives

and sibilants give clarity to the words sung. Bass has more punch and snap, and

there’s a more natural decay of the harmonics that follow a drum stroke. Improved

percussive sounds deliver better pace, rhythm, and timing, which gets the foot tapping.

Comparing the original 1973 CD release

of Linda Ronstadt’s Don’t Cry Now with Mobile Fidelity’s new

remastering of it shows how not-so-subtle differences can separate a remastering from the

original. The first thing I noticed was the MoFi’s more expansive soundstage. At

normal levels, Ronstadt’s distinctive voice is more open and crisp, and appears more

forward in the mix, with lifelike height, presence, weight, and harmonic texture. Many

people perceive harmonic texture as a sweetness, or euphonic quality. Here, both

Ronstadt’s voice and the guitar, on such tracks as "Love Has No Pride" and

"Desperado," exhibit a richer harmonic tone than the standard release. This is

not surprising -- DRC can effectively mask overtones. This quality gives the MoFi remaster

a more involving, more spine-tingling, and therefore more enjoyable sound. Vocal

intelligibility is also improved. This makes sense -- the natural overtones of plosives

and sibilants give clarity to the words sung. Bass has more punch and snap, and

there’s a more natural decay of the harmonics that follow a drum stroke. Improved

percussive sounds deliver better pace, rhythm, and timing, which gets the foot tapping.